IntroductionThis is the complete Introduction to Carfree Cities.The limitations of HTML make it impossible to format it in the same way as it appears the book. You may view actual specimens (200kB file) from the book.

|

| Piazza San Marco, Venice, 1997 The main text of this book is set in a typeface called Bembo, first cut in Venice by Francesco Griffo in 1495. Griffo was employed by Aldus Manutius, a classicist who established the Aldine Press in Venice. The books of this press helped spark the Renaissance. Lawson, 74-77 |

INTRODUCTION |

| See especially Cities and the Wealth of Nations | Mankind first settled in cities about 7000 years ago, and cities have served as the cradle of civilization ever since. I believe that the future of cities is assured. Culture is hosted by cities because only cities can support great libraries, symphony orchestras, extensive theater districts, major-league sports teams, and vast museums. Cities also provide the principal setting for economic activity. Jane Jacobs believes that the wealth of nations is generated mainly by innovators located in urban areas with the broad infrastructure base needed to support the establishment of new enterprises. Innovators need a vast range of goods and services close at hand, plus, of course, good transport and communications. Only cities can provide such depth of resources. |

| Cities ought to be places where great buildings and lively outdoor spaces are found, which was usual until modern times. The European capitals still provide many wonderful examples of good urban spaces. Piazza San Marco is perhaps the greatest of them all, peaceful yet vibrant. Most Italian cities have gorgeous squares, a few of which have been protected from cars. New York, Boston, and San Francisco still have great districts, as did most US cities until cars and suburban sprawl bled their hearts dry. | |

|

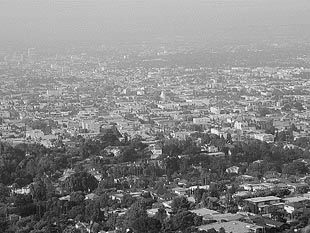

Auto-centric cities are those based on transport by private automobile. Infrequent buses offer indifferent public transport. Car ownership is nearly essential, even for the poor. Los Angeles is the archetype. |

When thinking about cities, we must remember that suburbs are an urban, not rural, form. This reality clashes with the suburban leitmotif: fleeing the city to live in the countryside. However, few US suburbs still offer even the illusion of country life, and they depend on central cities for work, health care, and culture. The "national automobile slum" is thus the worst of both worlds: vast areas of forest and farmland are turned into low-density residential neighborhoods organized around automobile transport. Inhabitants of these auto-centric areas must drive great distances through repulsive surroundings to reach virtually every activity. |

|

|

Rural areas supplied the people, food, and resources to fuel the urban engine that produced the bulk of our technical advances. Although some of these advances turned out to have a dark side, there can be little doubt that technology has generally improved our lives, and we have our cities to thank for this. Predictions abound that virtual reality will reduce the need for physical presence and thereby the need for cities. While virtual reality will provide an alternative to face-to-face meetings for some task-focused groups, I believe that most people will find it an unsatisfactory substitute for personal contact. I am no technical reprobate: I have computers in my home, make extensive use the Internet, and enjoy playing computer games. But for me, no form of virtual reality will ever replace a pleasant evening stroll among the neighbors. I believe this is true for most people. For as long as people continue to want to meet in person, the future of cities is assured.

|

|

|

Cities & CommunityIn the New World, quite a few social groups have been so marginalized that they no longer have a true place in society. At the same time, some of the richest members of society have in essence completely withdrawn from public life. They live in gated communities, to which the poor are only invited to wash the floors, clean the pools, and tend the gardens. Some rich people only venture into the outer world when isolated in their cars, and then often to travel to members-only venues. |

|

In late 1999, many activists gathered in Seattle to protest secret negotiations being conducted by the World Trade Organization. Police mishandled the demonstrators, almost all of whom were practicing nonviolence. The confrontation has become known in some quarters as the "Battle of Seattle."

|

The French Revolution showed how dangerous it is for a privileged aristocracy to isolate itself from the population. No one who could say "let them eat cake" could possibly have had any understanding of what life was like for nearly all her subjects. I fear that a divide is arising in modern Western societies as the degree of segregation and alienation rises. As the "Battle of Seattle" showed in 1999, leaders must maintain some sort of common ground with the rank-and-file or risk unexpected and unpleasant confrontations with those who feel that they have been disenfranchised. The splendid isolation in which most leaders live surely does not increase their sensitivity to the plight of their constituents. Most leaders are surrounded entirely by people like themselves: rich, powerful, well-educated, and assured of a place at the table. This is true not only among national leaders but also at much lower levels of government. Almost all leaders travel by car and rarely rub elbows with those who elected them. The restoration of streets as public spaces used by everyone will help to assure that citizens from every part of society maintain at least a modicum of contact with one another and to promote conditions under which civilized societies can flourish. |

Cities & TransportThe amount of space that an urban transport system absorbs has a critical effect on urban form. Cars are the most space-intensive form of urban transport ever devised and have forced cities to expand into rural areas. In many cities, attempts to accommodate cars required the construction of urban highways that severely damaged the neighborhoods through which they were driven. Other means would have provided better transport at far lower costs. Rapid improvements in urban and intercity rail systems during the period 1850–1935 offered mankind the best transport that had ever been seen, but in the USA, cars began as early as 1915 to erode the quality of public spaces and to impede public transport vehicles operating on the streets. So began a long downward spiral in the quality of life in US cities. |

|

|

The delivery of freight in cities has been problematic since Roman times. The chapter on freight delivery proposes a means to deliver freight in our cities simply by extending the use of standardized shipping containers. Such containers are now routinely moved by the thousand around the globe aboard ships, barges, trains, and trucks. The means I propose merely extend existing, proven technology, much of it fully automated. The automobile industry has become such a large segment of the world economy that many fear any change that might threaten the continued production of tens of millions of cars each year. Any large decline in urban car usage will certainly cause major economic dislocations, so the change to carfree cities will require careful economic planning and implementation in phases (which is, in any case, almost essential). The auto industry will continue to sell millions of cars a year to those living in rural areas, for whom it is difficult to imagine any other practical means of transport.

Carfree Urban Areas |

|

|

Some will scoff at the viability of life in carfree cities, but remember that every city was carfree until about 100 years ago. Venice clearly demonstrates that carfree cities can at the very least continue to function in modern times. It is risky, however, to use Venice as the sole proof of the feasibility of carfree cities. Many regard Venice as a dying city and note the dramatic decline in population since 1945, from about 200,000 to around 75,000 in just 50 years. Venice is, in fact, a victim of its own success. The combination of the delightful carfree environment, together with a large helping of the world’s art and architectural treasures, has made Venice one of the world’s most popular tourist destinations. Rich people bought up many houses in Venice, and many of these buildings are vacant for most of the year. Other buildings have been converted to hotels to shelter the visiting hordes. Housing prices rose so much that many Venetians were forced to move to Mestre on the mainland, leading at least in part to the dramatic decline in population. Even in winter, however, Venice does not seem like a dead city: it feels like the bustling, good-humored small city that it is. |

|

Most large industry in Venice has relocated to nearby Mestre. Smaller industries, however, still continue to thrive. Murano, an island just north of the two main islands of Venice, has been a leading producer of fine glassware since 1291. Dozens of small glass factories still operate here, so it is evident that small industries with moderate freight requirements can survive despite the problematic freight system.

|

|

|

A reference design is a benchmark, used as a point of departure. Normally, a reference design is not actually built, although it should in principle be employable in some real situation. The reference design for carfree cities could be built without appreciable modification in several Dutch polders and other flat, sparsely-settled tracts. Local conditions will usually dictate substantial deviations.

|

Most difficulties that beset Venice are intrinsic to its location in the middle of a shallow lagoon or related to its unique place in history. When building new carfree cities or converting existing cities to the carfree model, we will usually be able to design around constraints of this kind. Venice serves us best when we regard it simply as evidence of the high quality of life that is possible in medieval cities: four-story buildings, crooked narrow streets, and relatively high density are in themselves no barrier to a high quality of life, so long as cars are not permitted to terrorize the streets. I would argue, in fact, that it is precisely these qualities of Venice that make it so successful, and many aspects of the "reference design" for carfree cities are indeed based on the Venetian model. To be sure, other models are also feasible: all that is necessary for the basic carfree design to work is to achieve a sufficiently high population density to support excellent public transport. This can be achieved in many different ways. At one end of the scale are the towering Modernist skyscrapers of Hong Kong and Manhattan. At the other end are low-rise, high-density urban areas like Burano (a small island near Venice) and the old lilong neighborhoods of Shanghai. (Most of the lilong areas have been demolished in favor of high-rise buildings, but when I was in Shanghai, the locals spoke longingly of the warm social environment that had characterized the narrow streets of these carfree areas.) Further evidence of the workability of carfree cities can be seen in Europe, where many cities have made parts of downtown carfree. In a few cases, such as Freiburg, most of downtown has been made largely or entirely carfree. These areas have been popular with residents and tourists alike, and the initial opposition of merchants has generally changed to strong support within a year or two: most merchants saw their business improve once the cars were gone. Some cities in the USA have also experimented with carfree areas, although usually on a more modest scale. Some of these experiments have been deemed unsuccessful and reversed, but it appears that most of the unsuccessful trials were in fact "transit malls," which is really another name for an outdoor bus station. Removing cars in order to replace them with diesel buses does little to improve the street in question. Finally, we must keep firmly in mind that carfree cities demand excellent public transport. Some existing examples of top-quality public transport will be cited later. The only barriers to achieving first-class service for all transit users are political: no technical problems remain to be solved, so long as the necessary population density is achieved. All that is lacking is the will to make the needed service improvements. |

|

|

A Failed ExperimentThe few good urban environments that still exist in the USA were built before the needs of cars subsumed centuries of urban planning craft. These areas are almost invariably the most beautiful parts of the city (usually also the oldest parts of town), and typically see the heaviest use. In fact, the desire for housing in these deeply-satisfying areas overwhelms the supply and drives up real estate prices. This pattern can also be seen in Europe. The experiment was supported by the most costly civil works program in history: the construction of the US Interstate highway system. Without fast highways connecting the center city to rural areas, the exodus to the suburbs could never have proceeded so far or so fast.

|

|

|

Even if sufficient resources can be found to sustain the experiment indefinitely, there remain many reasons to remove cars from our cities: cars are wasting our time, wrecking our lives, and destroying our societies. In the 20th century, cars have done more to damage our cities than wars, terrible as they have been. No city except Venice has been immune to the ravages of cars. Urban automobile usage amounts to an undeclared war between drivers and everybody else. Just as in a real war, there is a lot of "collateral damage." We see it around us every day in the form of the awful environments built since the needs of cars and their drivers came to dominate every aspect of urban planning. These ugly environments seem inseparable from auto-centric development. They have had a devastating effect on the civic functions of the public realm. These dreadful environments discourage people from spending time in public places and broadcast the message: this mess is so awful, nobody cares what you do here. It leads to isolation, cynicism, hopelessness, and antisocial behavior.

|

|

| See Donald Appleyard’s work for a thorough examination of the effects of cars on communities. | While many problems with cars are of a technical nature and therefore susceptible to engineering solutions, the most serious problems are intrinsic and cannot be solved by any application of technology. I regard the damage that cars do to social systems as the most serious problem they cause in cities. No technical improvement to cars can restore the vital function of streets as the host for community: as long as anything as dangerous and intrusive as cars and trucks rule our streets, civic life will vanish from the street. | |

| For more on life in contemporary US cities, see Jackson, Kay, and Kunstler. See also this book’s foreword. | At a deep level, Americans are finally beginning to understand that something is missing in their lives. The sudden emergence of suburban sprawl as a topic of national discussion indicates that many have realized that something was lost when sprawling suburbs replaced walkable, human-scale cities. This discussion is perhaps less evident in Europe, which was slower to adopt widespread car usage and where cars were never permitted to do as much harm to cities. (We shall see later that Le Corbusier proposed to demolish most of Paris in order to build highways and tower blocks. Fortunately, wiser heads prevailed.) | |

|

As evidence of the seriousness of our design errors, I offer the passion we now exhibit for the preservation and restoration of old urban neighborhoods. Today in the industrialized nations, almost any proposal that would damage these artifacts of civility is instantly shouted down. We have recently seen a spate of books proposing solutions to the urban transport crisis and the problem of suburban sprawl. While this marks the dawning of awareness that automobile usage in cities causes many intractable problems, the solutions so far proposed are only palliatives. This book proposes a solution that is at once radical and reactionary: radical because it proposes major changes to our cities, and reactionary because many of these changes are actually a reversion to urban patterns still widely applied just a century ago. |

|

A Solution |

||

|

A woonerf is a residential street to which cars are only admitted on the condition that they proceed at dead slow. Street furniture creates a winding path that effectively enforces this condition; high speeds are impossible, and most streets are dead ends.

|

The Dutch woonerf really does improve the quality of life for residents, based as it is on the presumption that cars are admitted so long as they proceed at a walking pace and do not disrupt other activities. However, the woonerf approach is not extensible beyond local neighborhoods because cars require reasonably high-speed streets in order to provide quick transport. The woonerf solution may also simply displace traffic from one street to another, such as happened in Berkeley, California, where some residential areas were turned into a maze of dead-end streets. Traffic that had used the local streets was simply displaced to the main arteries. A real solution to the problem of the urban automobile can only be achieved by moving cars entirely out of the city. Only by this means can we restore true peace in our streets and provide a safe environment where people are invited to linger, without fear of traffic. If we replace auto-centric urban transport with rail-based systems, we can retain and even improve our current levels of mobility at a cost both we and the environment can bear. A carfree city designed around rail transport would greatly reduce the resources currently consumed by urban transport while providing a fast, comfortable alternative to cars. In order to make effective use of rail systems, carfree cities will require a considerably denser pattern of living than the suburbs, but denser, carfree living can help restore community to our neighborhoods. The design for carfree cities provides a way to establish nearby parks and open space, regain peace and quiet in our homes and offices, and begin the reconstruction of social systems damaged when the automobile drove life off the street. The required density increases are by no means extreme: densities that are still common in European city centers are entirely sufficient. Even sprawling Los Angeles has a few neighborhoods that are more densely populated than the districts proposed for carfree cities. |

|

| The changes I propose are far-reaching indeed: the complete removal of cars and trucks from city streets is as sweeping a change as I can imagine. While many compromises with this radical approach are possible and probably quite workable, I think that we should adopt a policy of completely removing motorized traffic from city streets. Only in this way do we obtain the full benefits of carfree cities. However, Part III does consider design compromises that permit some level of continued urban car usage while still yielding streets that are entirely carfree. | ||

|

The reference design proposes a return to traditional forms of city building, because these forms have shown their worth through the ages and because people still seem to value these areas the most. However, many architects (and a few others) continue to believe that Modernism is mankind’s salvation. Modernism could be accommodated in its own district, as Léon Krier has proposed. The rest of us would be free to live elsewhere, in districts based on older, more comfortable patterns, such as those identified by Christopher Alexander. One element of the reference design in particular has aroused considerable opposition: my proposal to adopt Alexander’s pattern limiting building heights to four stories is strongly opposed by some, including a few people whose views I otherwise largely accept. While tall buildings are not essential to a successful city, there is no reason why a district could not be reserved for skyscrapers. In fact, the division of carfree cities into districts makes it easy to provide locations to accommodate a wide range of preferences. |

|

|

|

The message of this book is simple: Get the cars out of the cities. The rest is simply a proposal for how to achieve this. Other methods besides those I propose would probably also work, although some might require technically-advanced transport systems whose practicality has yet to be demonstrated. Any promising method should be tested. The more carfree areas that are developed in the coming decade, the better. Some efforts will doubtless work better than others, but even the attempts that do not achieve complete success will provide interesting environments and useful lessons. I believe that nothing will sell the idea of carfree cities better than the experience of carfree areas, and Venice is certainly the best advertisement for carfree cities that I have ever seen. Carfree cities can offer rich human experience, great beauty, and true peace. They can greatly reduce the damage we are doing to the biosphere. They permit the construction of beautiful districts in the manner of European city centers, with parks but a short walk away. Carfree cities are a practical alternative, available now. They can be built using existing technology at a price we can afford. They offer a real future for our children. |

|

Organization of the Book |

||

|

|

Back to Book Home

Go to Carfree.com

carfree.com

Copyright ©2000-2002 J. Crawford, except

Photographs of Los Angeles Copyright ©1999 Richard Risemberg